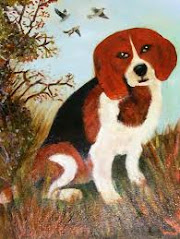

A tiny yellow paw darts out at me from the long row of metal cages on the adoptable cat wing of our local animal shelter. It is the summer of 1994, and I have come to the shelter in hopes of adding another kitten to my household. While vacationing in Key West a couple of months earlier, I found a litter of stray kittens under the steps of a museum, and brought one home. There are a couple of older cats at my house, but no youngster to play with the kitten. I thought she might benefit from having a playmate.

I turn to look at the small animal attached to the paw. A solemn little whiskered face peers up at me. She is a small wisp of a tabby, not more than a couple of months old. I reach my index finger through the bars and scratch her little chin. The kitten lifts her chin and purrs, her motor going strong. I tell her that she’s coming to live with me.

A few days later, after she’s been spayed and received her vaccinations, she is ready to leave the shelter. Because the kitten from Key West is named Blondie, I’m perplexed about what to name the new one. Since she’s yellow, Blondie would have been a good name for her. The synonym Goldie seems to fit my new baby.

To my disappointment, the two kittens don’t bond very well. They are generally indifferent to one another. Nevertheless, Goldie is a wonderful addition to the family. She’s shy on approach, to the point of being a “touch-me-not”, but she comes around in her own time and on her own terms. She protests when I pick her up and squirms until I put her down. When she decides she wants affection, Goldie lets me know with her chirpy meow, insistent head-butting, and the brush of her long ringed tail against my legs. She reaches out her paw and touches me, just the way she did at the animal shelter, in order to get my attention. I lean down and scratch her head. She purrs appreciatively, but still keeps a very serious look on her face.

She is a well-mannered, dainty little feline, very civilized and fastidiously clean. For a while, when I am living out in the country, all five cats living on the property catch mice. Some of my kitties make a game of chasing down the little rodents, batting them around and pouncing on them repeatedly before the kill. Goldie, not wanting to be left out, catches a mouse also but makes quick work of the hunt, putting a swift end to her prey's struggle, as though she wishes to be merciful to the small gray creature.

Our lives go on intertwined for more than ten years, until 2006. Goldie begins to vomit and lose weight. She is obviously not feeling well. After a couple of days, I hurry her off to the vet’s office. After blood tests, a sonogram, biopsies, and other tests, she is diagnosed with stomach cancer. This news hits me like a ton of bricks. I have never had a seriously ill pet before.

The next two months are a flurry of surgeries, feeding tubes, medications, bandages, and vet appointments. The vet gives me articles to read about research studies on feline oncology. She urges me to consider either intravenous or oral chemotherapy for Goldie, earnestly pointing out that this treatment can extend a cat’s life up to two years. She believes Goldie’s cancer may go into remission with treatment. I don’t know what to think. I know that chemotherapy sometimes makes life a living hell for humans suffering from cancer, and then they die anyway. I don’t Goldie to suffer, and I am concerned about what her quality of life would be like on chemotherapy. I ask the vet a hundred questions. Will the chemo make Goldie lose her hair? Will she continue vomiting? Will she feel sick all the time? How much will chemotherapy cost?

Unfortunately (or perhaps fortunately), before I can make a decision about chemotherapy, the cancer spreads to rapidly Goldie’s brain. All of a sudden she can no longer stand up unassisted without falling over on her left side. Her vision becomes impaired, and she cannot find her way to the litter box. I place her gently in the box and hold her steady her so that she can keep her balance while she relieves herself. Goldie growls when I approach her, refuses to eat, and secludes herself in an easy chair in the corner of our spare bedroom. She looks miserable. She is fussy about taking medication. I worry that her pain may not be adequately controlled.

I am forced to face the fact that it is probably best for Goldie to not keep going. There are worse things than death. Goldie is clearly suffering. I don’t think that either she or I can face the ordeal of chemotherapy, although I am glad for the advancements in veterinary oncology that can extend the lifespan of some cats with cancer.

As she goes gently to sleep in our vet’s office, I hold Goldie’s paw. She reached out to me with her paw at the animal shelter in 1994, and in the end it is my responsibility as her mommy to reach out to her and relieve her suffering. Reaching out with her paw was the behavioral trait that drew me to Goldie and brought us together. I whisper in her ear, thanking her for being my kitty, and telling her that I will always love her. I give her little yellow paw one last squeeze.

Wednesday, August 6, 2008

Friday, August 1, 2008

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)